First in an occasional series on how organizational interdependence affects the judiciary

Two recent stories illustrate how the structural interdependence of courts within a constitutional system can drive judicial choices and behaviors.

We start in Sandusky, Ohio, where Common Pleas Judge John Dewey appointed his personal court administrator as a deputy court clerk, a position that would allow the administrator to handle all filings in a sensitive case involving allegations of sexual assault. Judge Dewey further decreed that the case filings should remain sealed, meaning that the newly appointed deputy court clerk would be the sole gatekeeper of the records.

The decision angered the local media, which asserted a First Amendment right of access to the filings. This was not an ordinary case of sexual assault: the defendant was the local district attorney, and the public had an interest in the proceedings. To complicate matters further, under Ohio law court records are supposed to be handled by an elected official. Judge Dewey’s administrator was not elected, and Judge Dewey apparently did not inform the elected court clerk about his preferred arrangement. This decision caused enormous confusion in the clerk’s office, both as to why he did not tell the elected clerk what he was doing, and as to whether Dewey’s decision to appoint a deputy court clerk was even legal.

It is also unclear why Judge Dewey had been given the case, given that the defendant was a regular–indeed, institutional–participant in the Sandusky County court system. Typically, when a local attorney or judge is involved as a party in litigation, the case is assigned to a judge unaffiliated with that jurisdiction to prevent a judicial conflict of interest. Somehow, though, Dewey held on to the case for months even though it created a visible conflict with other cases on his docket that had been brought by the prosecutor’s office.

Judge Dewey finally recused himself in late September, noting that “Sandusky County Judges have a conflict in this matter as it may involve a Sandusky County elected official.” A retired judge was appointed to take over the case, and in early December the defendant took a plea deal that will keep him out of jail but require him to resign from his elected position.

So what was going on here? It’s hard to know whether Judge Dewey’s series of odd choices–not recusing himself from the outset, holding on to the case for months, and quietly appointing his administrator to have sole control over the court papers–was driven by ignorance or some sort of malfeasance. But whatever Dewey’s motivation, the situation was made possible by the tight institutional connection between elected officials within the local Ohio court system. Prosecutors, court clerks, and judges are all elected on partisan platforms. Prosecutors often seek judicial office. And the internal community is likely very tight-knit. In many localities the judge, court staff, and criminal attorneys spend so much time together on the job that they come to think of themselves as a team of sorts–what Professor Herbert Jacob called a “courtroom work group” — even though each participant has very different roles and responsibilities. (If you are familiar with the chumminess of the characters on the old “Night Court” series, you get the idea.)

The most benign view of Judge Dewey’s actions, then, is that he sought to protect the court system and its established courtroom work groups from external interference by a curious media. He assigned a trusted assistant to manage and seal records so that a sensitive matter could be handled without undue political pressure. And he overlooked a legal requirement to share that information with the elected clerk. If so, Dewey made a series of mistakes, but in service to the larger institutional scheme. This suggests that there is, perhaps, too much interdependence between the local institutions, such that it is impossible to truly separate them even when doing so would be in the interest of justice.

Of course, it may well be that the benign view is not the correct one, and that Dewey was protecting a prosecutor friend by knowingly, and improperly, taking over his case, and then hiding the details from the media. That certainly seems to be the view of the local paper, which has called for a deeper investigation. But even in this scenario, the situation was exacerbated by the interrelationship of the courts, the prosecutor’s office, and the voting public.

The only clear corrective to this type of problem is vigilance. Those inside the court system need to recognize when their interdependencies can erode the judiciary’s legitimacy or moral authority, and take proactive steps to address them. Those outside the system need to use their powers–formal or informal–to identify potential abuses and call for change. That process is playing out now in Ohio, hopefully with positive results for the future.

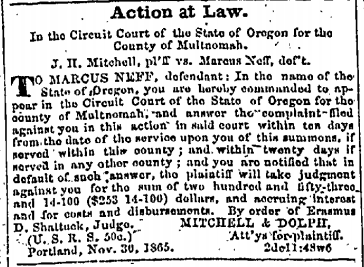

The Hartford Courant reports that the Connecticut state courts will no longer require parties to publish court notices in local papers, effective January 2. Instead, notices will be published in a dedicated court website.

The Hartford Courant reports that the Connecticut state courts will no longer require parties to publish court notices in local papers, effective January 2. Instead, notices will be published in a dedicated court website.