The Hartford Courant reports that the Connecticut state courts will no longer require parties to publish court notices in local papers, effective January 2. Instead, notices will be published in a dedicated court website.

The Hartford Courant reports that the Connecticut state courts will no longer require parties to publish court notices in local papers, effective January 2. Instead, notices will be published in a dedicated court website.

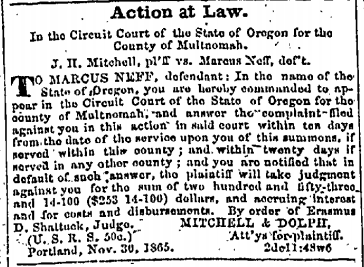

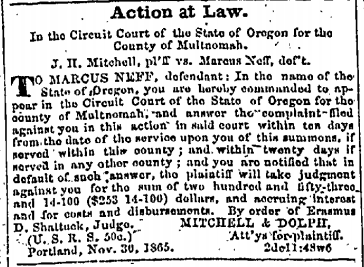

The practice of court notice by publication, sometimes called constructive notice, goes back centuries. It is designed to assure that all interested parties are informed of legal proceedings, especially when those parties cannot be found personally. Indeed, constructive notice played a central role in two of the most famous Supreme Court cases in history. In Mullane v. Central Hanover Bank & Trust Co. (1950), the Court signed off on constructive notice for parties who could not be reasonably ascertained at the time the suit was filed. In Pennoyer v. Neff (1877), the infamous bane of many a first-year law student, the Court based its personal jurisdiction analysis on the premise that constructive notice alone was not enough for the Oregon courts to exercise power over an out-of-state defendant.

Constructive notice is founded on the assumption that if notice is published somewhere, the interested parties are reasonably likely to learn about the proceeding. That itself is a bit of a fiction — the notice in Pennoyer v. Neff was published in a local religious publication called the Pacific Christian Reporter — hardly a paper of major import or geographical reach. But with the unquestioned dominance of the internet in our lives, and the ongoing struggles of the newspaper industry, it is probably more fair to post notices online that in the paper anyway. Newspaper publishers might be rightly angry about the development, but with 2020 on the horizon, it seems sensible for the Connecticut courts to embrace the twenty-first century.

Pictured: The newspaper notice in Pennoyer v. Neff

The Hartford Courant

The Hartford Courant